Structural Racism and the Food Environment

Food insecurity is the state of being without reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food.

- In 2013, 50 million Americans (14.3 percent) were food insecure.

- In Richmond, VA, 20.3 percent of city residents experience food insecurity.

- According to the USDA, 60,545 Richmond residents lived in a food desert in 2015

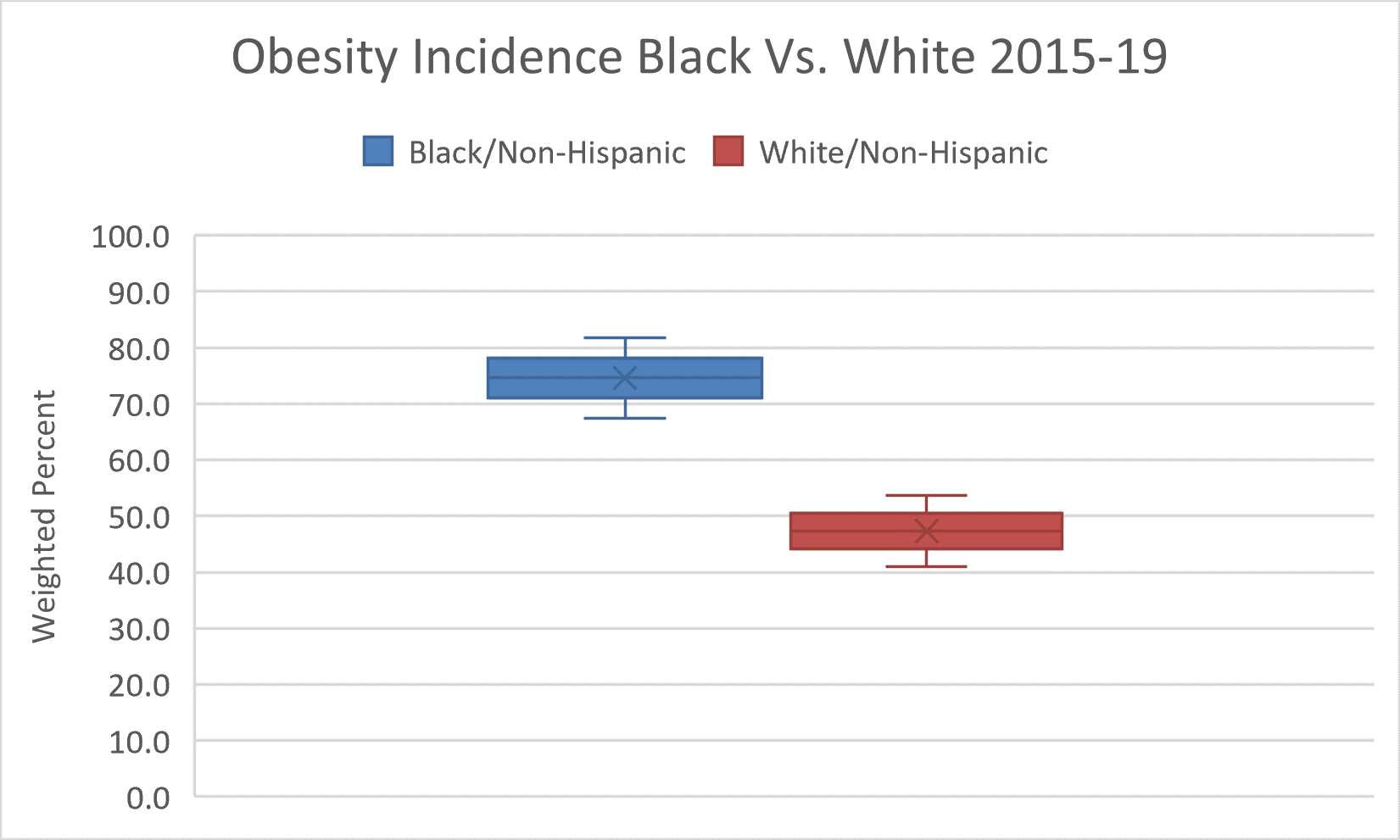

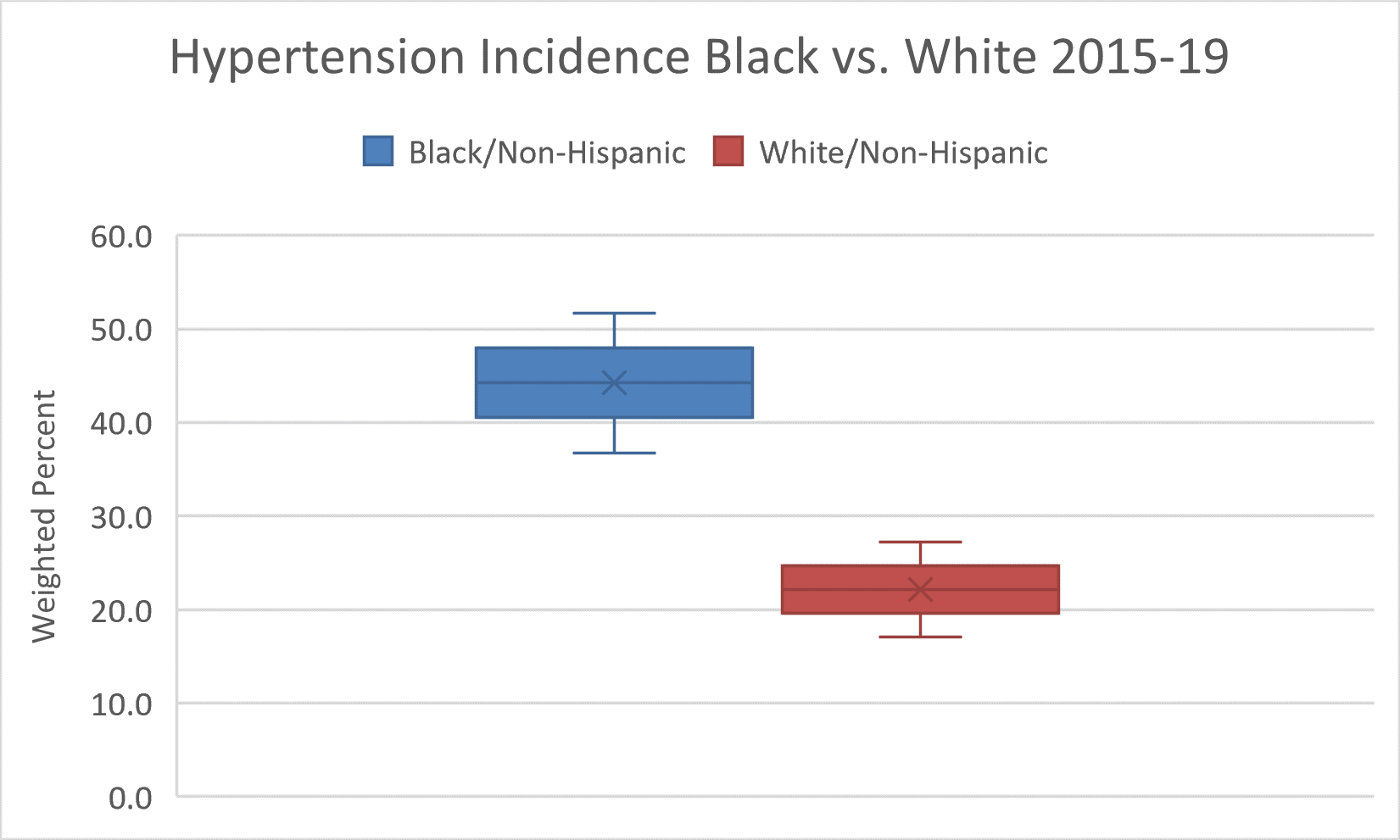

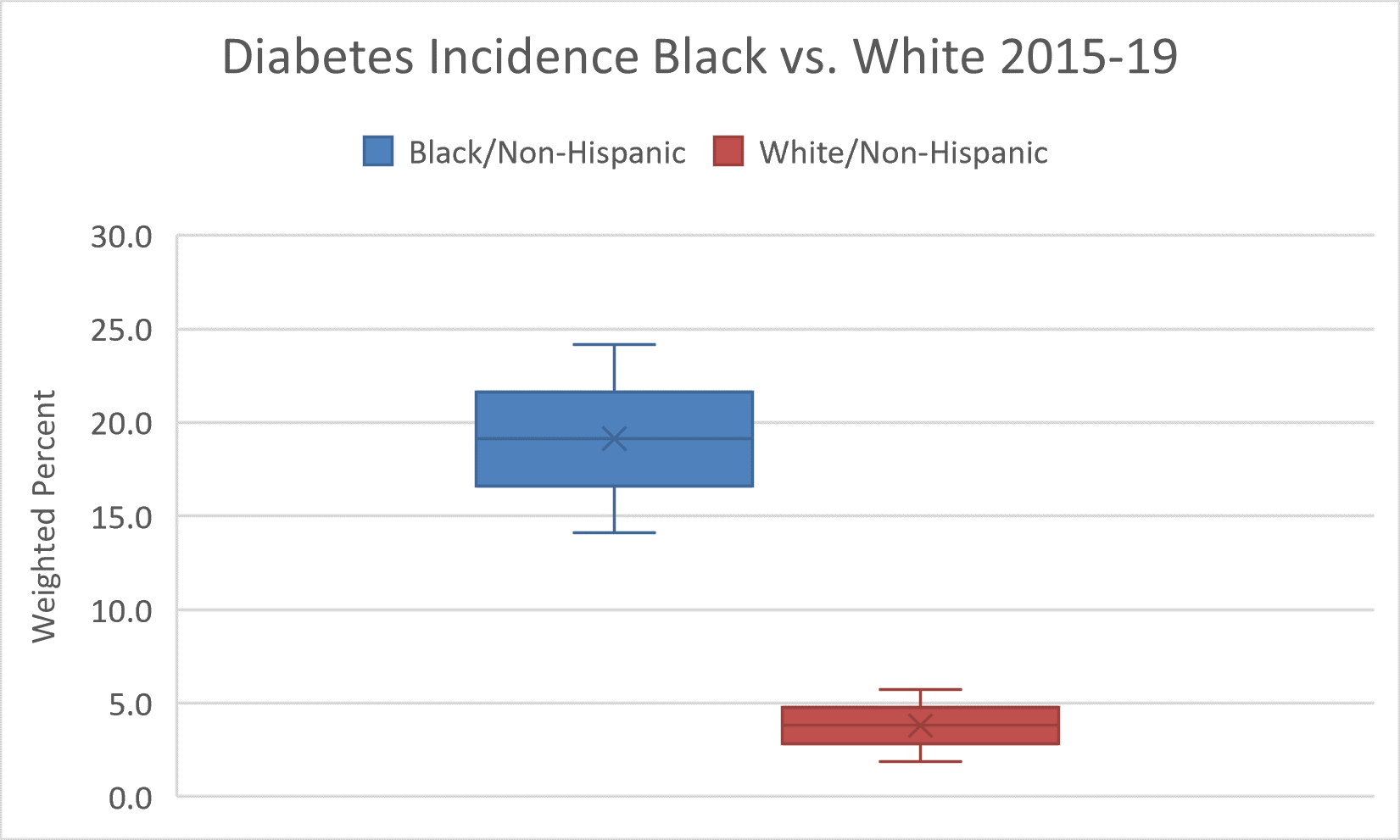

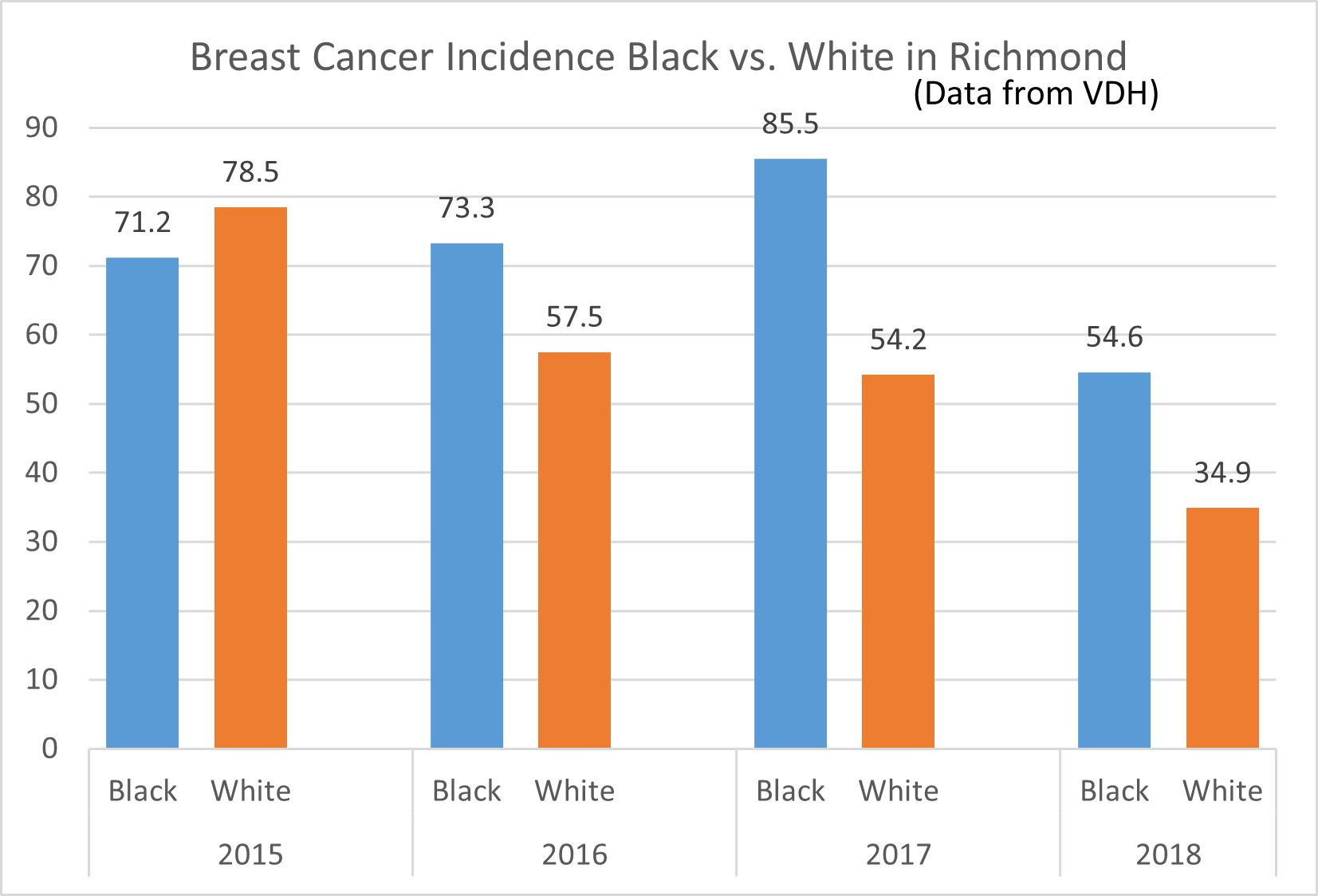

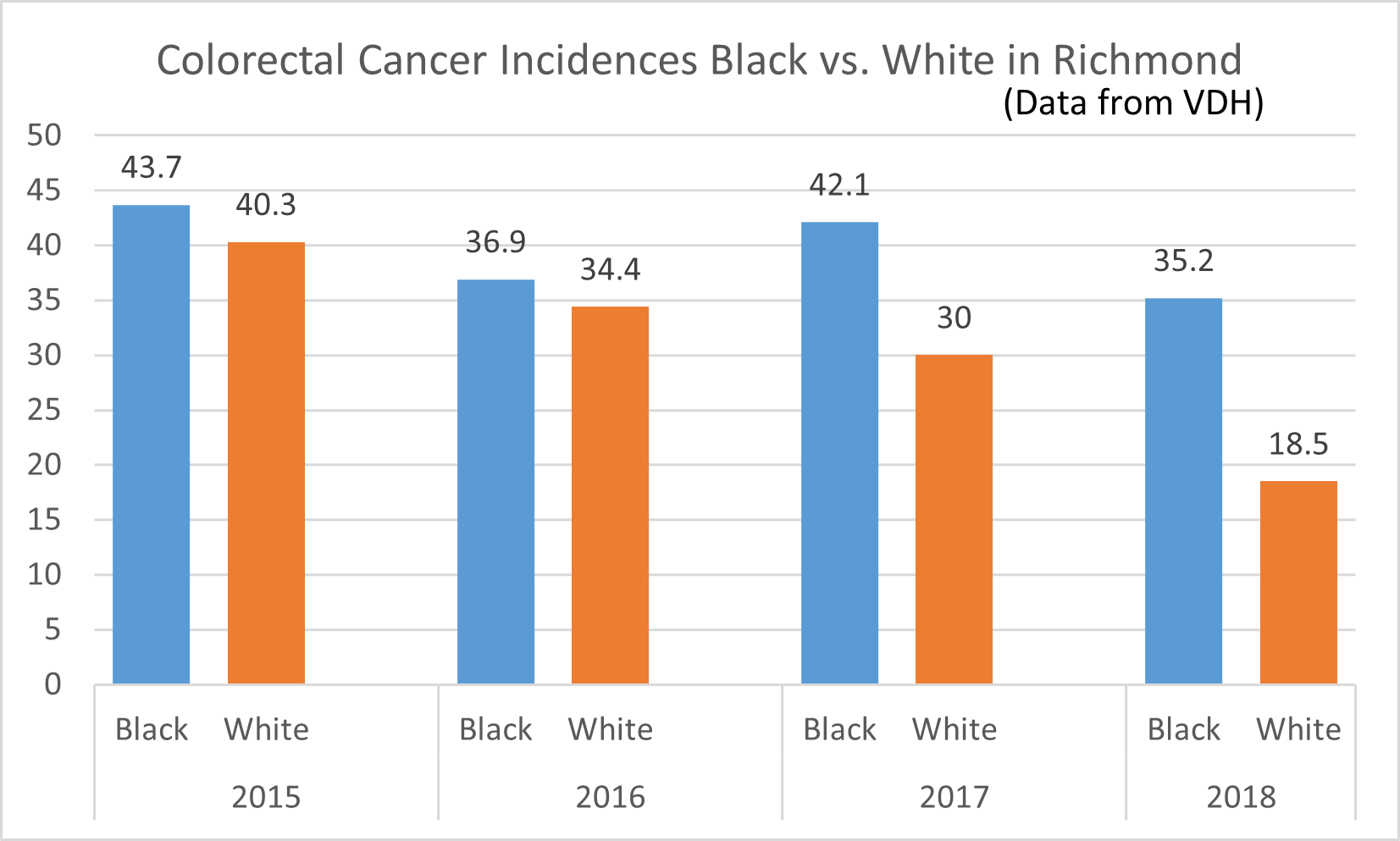

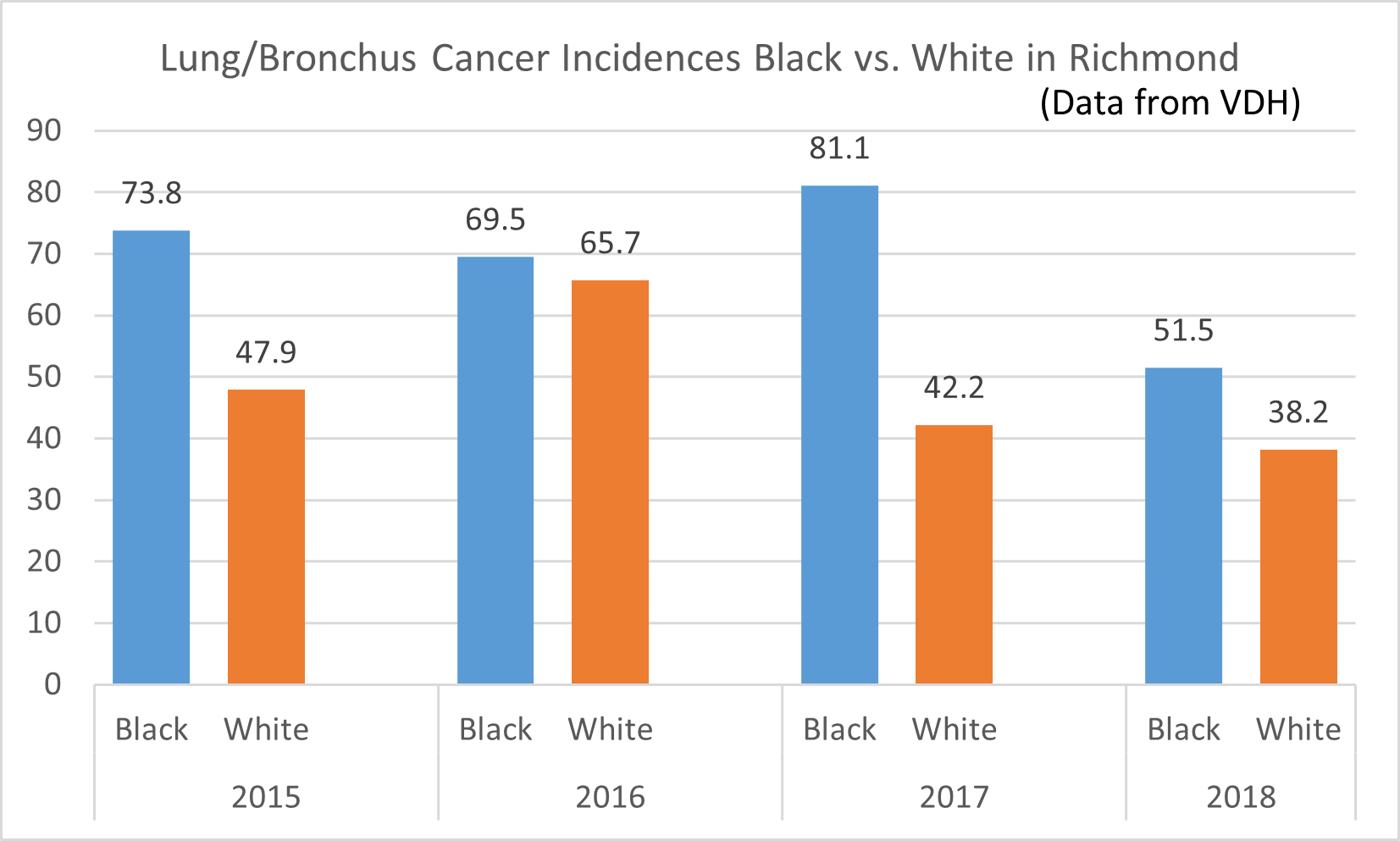

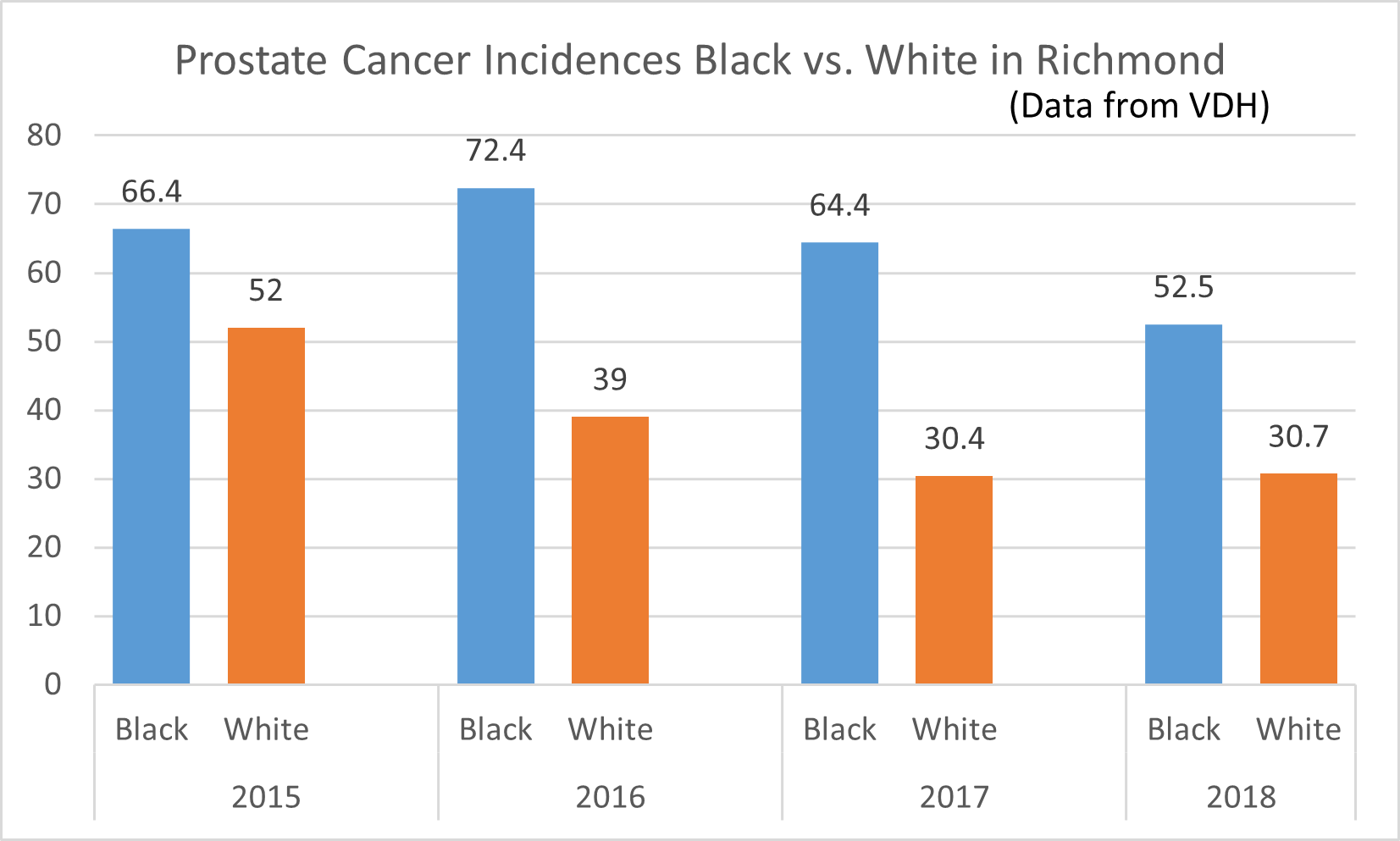

Poor food environment and food insecurity among African American individuals, resulting from social inequities and systemic issues, further contribute to chronic disease disparities by race/ethnicity.

- An estimated 22.5 percent of African American households are food insecure compared to White, non-Hispanic households (9 percent).

This module will describe the historical roots of food insecurity and health disparities in Richmond. It will highlight the role of racialized policies within Richmond in the construction of food desert conditions and, subsequently, disparities in chronic disease.

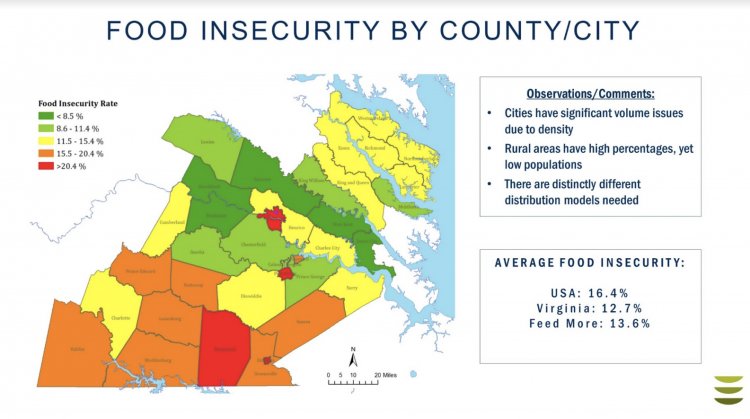

FeedMore and partner food bank Healthy Harvest cover 29 counties and five cities in Central Virginia. (Image: FeedMore)

Learning objectives

- To describe food insecurity and its historical ties to health disparities in Richmond.

- To understand how structural racism is manifested in the food environment.

- To identify resources to aid health care practitioners to address food insecurity.

NOTE: Users who are pursuing the Unlocking Health Equity badge, credit through the VCU Health System DEI learning requirement, or those who would like to claim continuing education credit must complete and submit the Reflection Activity at the bottom of this page. Please visit VCU Health Continuing Education for more information.

Learning materials

We ask that you spend an hour reading and viewing the materials below.

Food Insecurity in Richmond

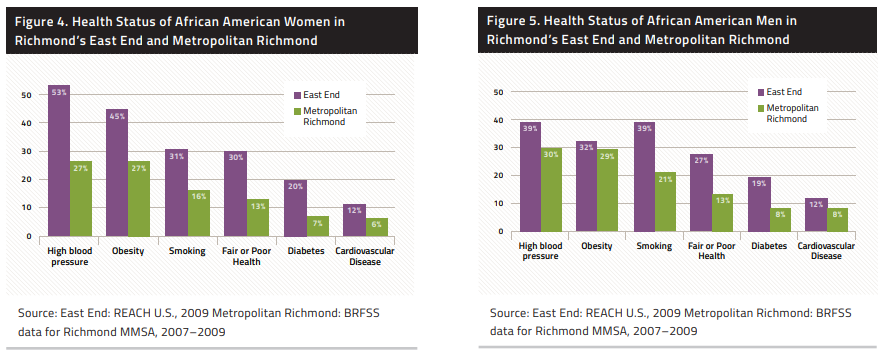

Healthy eating is key in preventing and managing chronic illnesses, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Yet, the food environments in which African Americans live are often characterized by fewer supermarkets, more fast food outlets, poorer quality goods, longer traveling distances, less fresh produce, and higher prices for nutritious foods.

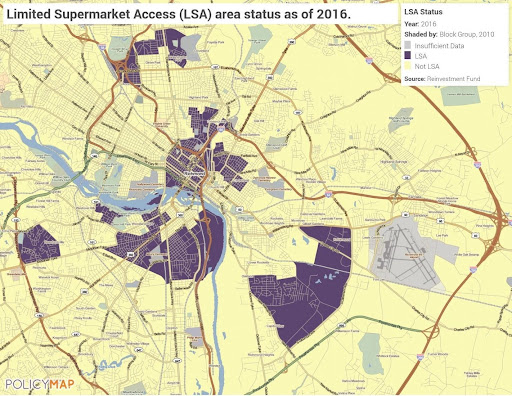

The presence of a supermarket could lead to a 32 percent increase in fruit and vegetable consumption among African Americans, but geographic isolation and historic zoning laws make supermarkets sparse in neighborhoods with predominantly African American/Black residents in Richmond—namely the east and south sides of the city.

(Image source: www.policymap.com)

Learn about zoning and food outlets nationwide in this 6 page research brief from Bridging the Gap.

Resources

We ask that you spend the hour reading and viewing the resources above and viewing as many of the linked resources below as possible prior to completing the reflection activity. Reflections will be evaluated, and individuals may be asked to resubmit if answers are incomplete or do not meet the length requirement.

For an overview of food insecurity, how it's measured, and its relation to health outcomes, read the Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes from Health Affairs article.

The burden of obesity and its related racial and ethnic disparities is outlined in this essay for Preventing Chronic Disease at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Visit Renew Richmond to watch how youth build healthy communities.

Recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Department of Agriculture detail American households’ economic well-being and hardship in 2020 and illustrate persistent racial inequities in food insecurity.

This academic article summarizes what is known about the effects of food insecurity on child development. It then considers how food insecurity harms children and explores both direct pathways through child health and indirect pathways through parenting and parent well-being. Finally, after reviewing existing policy for reducing food insecurity, we provide suggestions for new policy and policy-targeted research.

Read this report to learn about the most recent 2021 policies combating food insecurity and to end hunger in Virginia.

This academic article reviews how racism is a fundamental cause of food insecurity.

This rapid research article using 2020 U.S. Census survey data shows food insecurity during COVID-19 in households with children by racial and ethnic groups.

Time to reflect on what you have learned

To get started, click here.

Reflection activity directions

Users who are pursuing VCU’s History and Health; Racial Equity badge, credit through VCU Health System DEI learning requirement or those who would like to claim continuing education credit must complete and submit the Reflection Activity. The form asks the user to submit basic biographical information (e.g., name, department) and to answer one of the following 3 prompts. Your response must be a minimum of 250 words.

Let’s consider 3 pillars of food insecurity:

- Food availability: sufficient quantities of food available on a consistent basis.

- Food access: having sufficient resources to obtain appropriate foods for a nutritious diet.

- Food use: appropriate use based on knowledge of basic nutrition and care, as well as adequate water and sanitation

PROMPT OPTION 1: There are a number of structural factors in the food environment that drive eating behaviors. What are some of these factors related to food availability, access, and use? How can healthcare providers be better partners for patients in achieving healthy eating within the context of systemic barriers in the food environment?

-OR-

PROMPT OPTION 2: Individuals may navigate the food environment based on their broader lived experiences, for example, experiences of discrimination. What is one way that healthcare providers can be responsive to these concerns?

-OR-

PROMPT OPTION 3: Let’s consider the experience of a 55-year-old African American woman recently diagnosed with diabetes. She is well-educated and works in a high-stress job. Despite her best efforts to eat healthy foods and to exercise, she still hasn’t quite been able to lose the weight that her doctor has insisted is essential to turning her A1c in the right direction. She really doesn’t want to start medication, but understands that if she can’t get her numbers under control she may need to.

- What are some important questions to ask the patient to devise next steps?

- How might the provider partner with the patient in their care?